The name “Stu Green” is fictitious. But everything else about him is real. He grew up near Cornwall and almost died from an overdose.

The name “Stu Green” is fictitious. But everything else about him is real. He grew up near Cornwall and almost died from an overdose.

Stu Green was stretched out on his back at Arden Hill Hospital. He could hear his mother and his brother. They were talking to him, but he couldn’t answer. He couldn’t move; he couldn’t even open his eyes. The doctor opened them for a moment and then let them shut.

Stu Green was flat-lining. His heart had stopped; he had no pulse. Everything was fading.

Seeing no sign of life, the doctor was about to give up. But a nurse prevailed. “Let’s give it one final try,” she pleaded, as she applied the defibrillator for the eighth time. The device jolted the patient back to life.

Stu Green talks to Editor

Ken Cashman

That was almost five years ago. Sitting at a restaurant near his home, Stu Green retells the story to confirm what he has learned. “If you use heroin,” he says, “there are only three possible outcomes — you can die, you can go to prison or you can quit.”

The options weren’t always that obvious. Now 33, Mr. Green wishes he could go back and talk to himself at 18. His life might have been different. “I didn’t even get to enjoy my 20s,” he laments. “I was just doing dope. I traded those years for a needle.”

It seemed innocent at the start. As a high school student, it was easy to get Percocets or other prescription drugs. He got them from friends, who probably raided their parents’ medicine cabinets. The pill didn’t seem addictive, and the highs were rewarding. By the time he was 18, he was doing it every day. And he was switching to oxycodone.

“It bridged the gap to heroin,” he says in retrospect. He would scrape off the coating, fold a dollar bill around it, and then smash it with a lighter so he could sniff the remains.

It was good, but heroin was cheaper and more readily available. He could get it for $10 a bag in Paterson, N.J., or he could get 10 bags wrapped in a rubber band for $70.

In the beginning, he only used a quarter or a half a bag at a time. “You’d get such a good feeling,” he recalled, “that you knew you were going to do it again.”

“If you use heroin there are only three possible outcomes — you can die, you can go to prison or you can quit.”

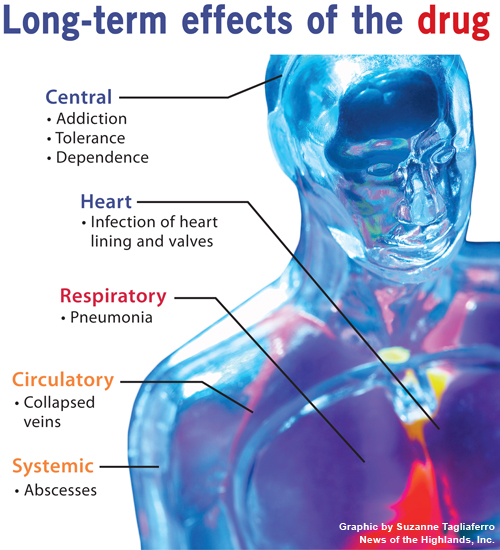

But tolerance of the drug builds quickly. After a while, a fraction of a bag isn’t enough. It no longer produces a euphoria. Mr. Green kept increasing the amount until he was injecting himself with the contents of five to 10 ten bags at a time.

The withdrawal was agonizing. Twenty-four hours later, there were muscle spasms and constant sneezing. “It’s like the worst flu,” Mr. Green said, “but you can’t sleep so you can’t escape it. It drives you insane.”

There were other reasons to stop. Several young people in the community had died from overdoses. Mr. Green could name at least five of them. But it didn’t deter him. “When you’re that into it [heroin or drugs],” he said, “safety is not a priority. It’s all about getting that next high.”

He had a few bad experiences before the incident that almost killed him. On a trip to Paterson, he failed to hook up with his usual dealer. So Mr. Green detoured to another street, purchased the heroin from someone else and ingested the usual amount.

But heroin differs in strength from one dealer to another. The bags (or “glassines”) are stamped, but you can’t always trust the markings. There are no regulators.

But heroin differs in strength from one dealer to another. The bags (or “glassines”) are stamped, but you can’t always trust the markings. There are no regulators.

Driving home from Paterson, Mr. Green fell asleep at the wheel. He wasn’t hurt, but he received his second felony DUI and lost his license for five years.

His life was in a tailspin, and besides the physical side effects of the drugs, he was suffering from depression. “Everything was bothering me,” he admitted. “I felt like I wouldn’t mind taking a break from life for a while.”

During one of these down times, he broke open a Fentanyl patch and chewed the contents, forgetting that he had recently taken a Xanax. The two don’t mix. His older brother found him on his feet, slumped against the wall and unconscious.

The defibrillator saved his life, but his medical problems weren’t over. He was on dialysis for a month, and in the hospital for two months. He suffered permanent nerve damage, and that total experience is what it took to end his addiction.

He went home with pain killers and took them for two-and-a-half years, but he didn’t abuse them. His mother filled the prescription and left him a daily ration, which he didn’t exceed.

He still had no license, but a neighbor gave him a job and the two of them traveled to customers together. Time passed, but the urge to use heroin didn’t. “I still think about it,” he admitted during the interview, “but if you put it in front of me today, I’d throw it in the garbage.”